After genocide comes chronocide

There exists no footage of the massacre of 33,771 Jews that took place on September 29–30,1941 in Babi Yar, a deep ravine northwest of Kiev, the capital and most populous city of Ukraine.

And yet Babi Yar. Context is based entirely on archival footage as it reconstructs the historical context of this tragedy by documenting the German occupation of Ukraine using the events leading up to the massacre and the aftermath of the atrocity of September 29–30,1941 when Sonderkommando 4a of the Einsatzgruppe C, assisted by two battalions of the Police Regiment South and Ukrainian Auxiliary Police, and without any resistance from the local population, shot dead in the Babi Yar ravine in the north-west of Kiev 33 771 Jews.

Scriptwriter/Director Sergei Loznitsa presented the film, a coproduction of The Netherlands and Ukraine, in Cannes Film Festival 2021 where it won the Special Jury Prize, the L’Oeil d’Or for Best Documentary.

At his press conference he said, “When memory turns into oblivion, when the past overshadows the future, it is the voice of cinema that articulates the truth. Such events push the artist to tell the story in a way that is interesting to people. Cinema brings people into the event and changes our perception. “

Says Loznitsa, When I put together the story of Babi Yar, I tried to reconstruct the historical context of life in German occupied Kiev. A lot of German officers and soldiers had brought with them amateur film cameras and filmed daily life in the city. This footage wasn’t suitable for propaganda newsreels, but I find this material the most interesting and fascinating of all. You get to see some fragments of daily life in Kiev in 1941–1943. I believe that it is crucially important to connect the tragedy of the extermination of the entire Jewish population of Kiev with the realities of life under German occupation.

The footage comes from a number of public and private archives in Russia, Germany and Ukraine. We have been researching this material quite extensively: our researchers worked at the Russian State Archive in Krasnogorsk (RGAKFD), at the Bundesarchiv and at a number of regional archives in Germany, and also we managed to access some private collections. The quality of the footage differed greatly. Some material was in a reasonably good condition, while some other reels were seriously damaged. The restoration work lasted for several months.

Some of the footage I work with has been buried in the archives for decades — nobody has ever seen it. Not even historians, specialising in the Holocaust in the USSR. One such episode is the explosions of Kreschatik in September 1941. Kiev’s central street was mined with remote controlled explosives by the NKVD (Soviet secret service) before the Red army had retreated from Kiev. The detonations of the explosives were carried out a few days after the Germans took the city. There were civilian casualties, and thousands were left homeless. The Soviets, who planted the bombs, did not consider human casualties and mass destruction as a significant factor in their military planning.

Another rare piece of footage, which I use in the film, is the footage of the last public execution in Kiev in January 1946. Twelve Nazi criminals were hanged in the city’s central square, which was then known as Kalinin square. 200 000 residents of Kiev gathered in the square to watch the execution. The whole scene has a very medieval feel to it. Or, perhaps, biblical — “an eye for an eye” …

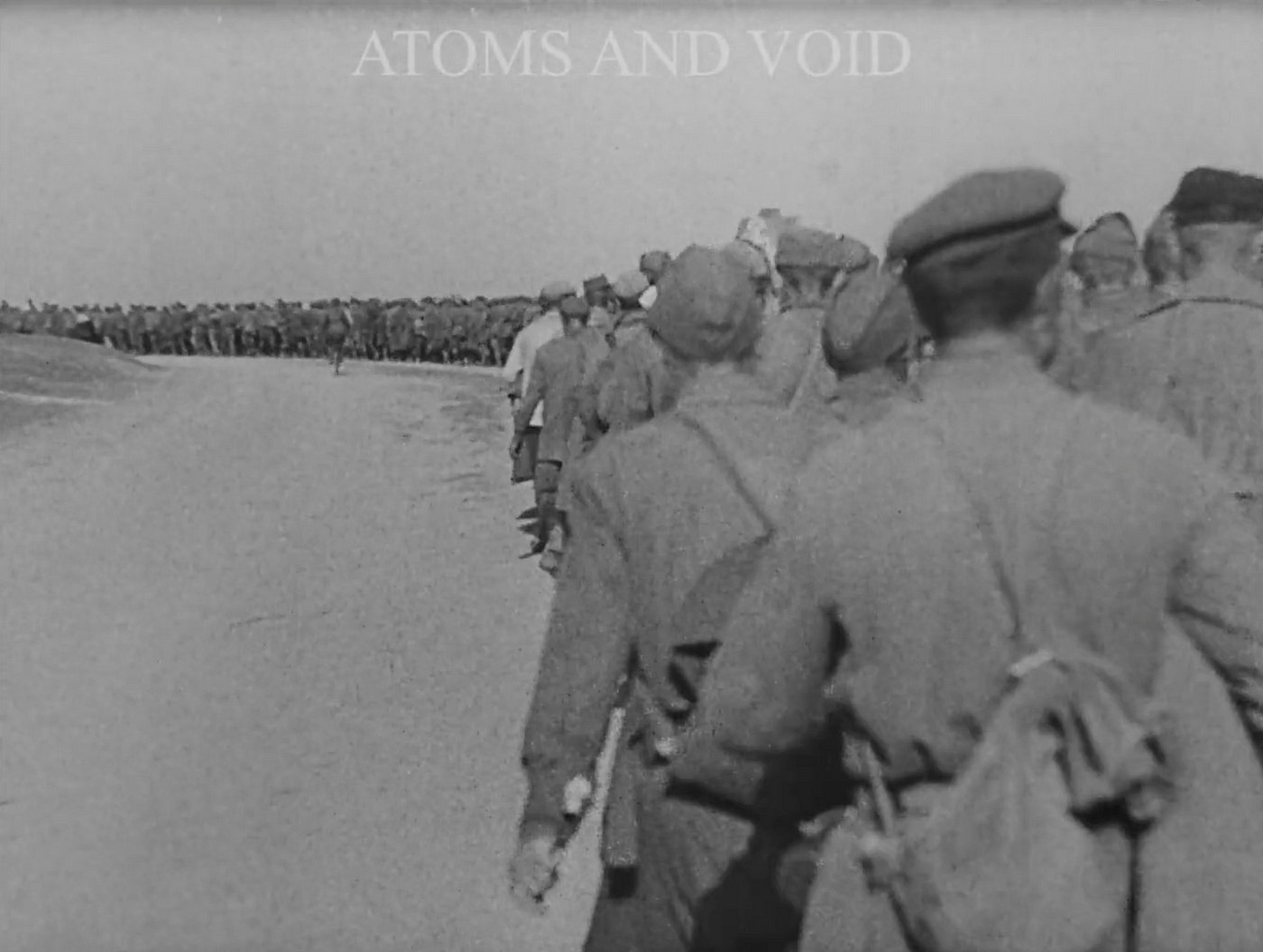

What 33,771 bodies look like can only be imagined through this documentary’s use of footage of the masses of Soviet prisoners of war (more than 600,000) marching, most of whom never returned home, or of citizens digging ditches for miles and miles, including women stripped to their underwear, barefoot, or the 1 million citizens of Kiev who turned out for the public hanging of the Nazis who ordered and carried out the massacre of the Jews.

The initial shock one had long ago on seeing the photographs which were first shown as proof of the Holocaust, bodies piled on one another, photographs which today seem to have lost their original shock value as we become immune to brutality seen over and over again, is replicated during a prolonged experience watching Babi Yar. Context. Its use of the archival footage depicting the masses and masses of puts us, the viewer, into a state of silent shock. The impact recalls my emotional reaction on seeing photographs of ‘Miners in Brazil’ by Sebastião Salgado in1986 on view at the Tate.

The film opens with an explosion and a black and white interstitial card reading “June 1941 Soviet Ukraine”. One hears a distant yell and a dog barking, a vague mix of human voies. A peaceful village burns as does the power plant. Endless billows of smoke spread across the country side. People quietly gather in the city to watch planes overhead, and a loudspeaker which says, “Moscow calling with a special broadcast. Cititens of the Soviet Union, on June 22, 1941 at 4 am…”

Germans move in and the people greet them with waves and the smiling Germans say “danke” as they are given bouquets of flowers. As people cheer, they happily tear down the posted of Stalin.

One sees male prisoners gathered on the ground and hears a German say, “He can’t walk. What will we do with him?”

One sees beautifully photographed masses of men, prisoners or Jews? Surrendering or being arrested. A color still photograph shows ruined houses and women left among ruins, the ruined bridge, a house burning, dead soldiers and civilians.

Shortly after the Wehrmacht occupied the city, a team of Soviet secret police (NKVD) dynamited most of the buildings on the main street of the city, where German military and civil authorities had occupied most of the buildings; the buildings burned for days and 25,000 people were left homeless.

Allegedly in response to the actions of the NKVD, the Germans accused the Jews of collaborating.

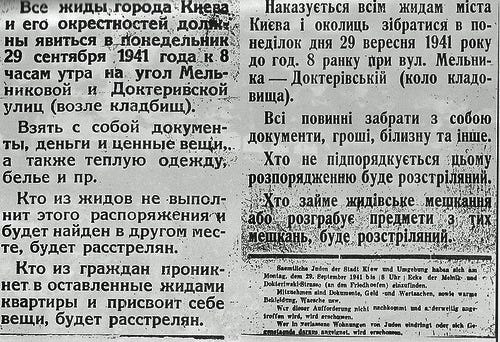

On 26 September 1941 the following order was posted:

All Yids of the city of Kiev and its vicinity must appear on Monday, September 29, by 8 o’clock in the morning at the corner of Mel’nikova and Dokterivskaya streets (near the Viis’kove cemetery). Bring documents, money and valuables, and also warm clothing, linen, etc. Any Yids who do not follow this order and are found elsewhere will be shot. Any civilians who enter the dwellings left by Yids[a] and appropriate the things in them will be shot.

Expecting 5 or 6,000, nearly 34,000 reported and were taken to Babi Yar and massacred. In the months that followed, thousands more were taken to Babi Yar where they were shot. It is estimated that the Germans murdered more than 100,000 Jews at Babi Yar during World War II, wiping out the entire population.

As an aside, and not included in this documentary, which is not a political statement in any way, several attempts were made to erect a memorial at Babi Yar to commemorate the fate of the Jewish victims. All attempts were overruled. A turning point was Yevtushenko’s 1961 poem on Babi Yar, which begins “Nad Babim Yarom pamyatnikov nyet” (“There are no monuments over Babi Yar”); it is also the first line of Shostakovitch’s Symphony №13. An official memorial to Soviet citizens shot at Babi Yar was erected in 1976.

Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial Center, an international non governmental organization, was established in 2016 in order to acquire, study and disseminate knowledge about the tragedy. It is planning a museum complex at Babi Yar, which will be one of the world’s largest Holocaust memorial centerss with research institutes, a library and a museum. But the first building to appear on the site is a house of prayer.

Babi Yar. Context is part of the Center’s efforts to use art as a medium for commemorating the Babi Yar tragedy, with a number of powerful sculptures and installations already unveiled during the past year at Babi Yar. The launch of the film is also an important component of the Center’s efforts to mark this year’s 80th anniversary of the Babi Yar massacre — Activities are taking place throughout the year across the world and will culminate in an international event including global leaders in October.

Sergei Loznitsa’s years of research culminates in what he considers just a starting point for discussion, not about history but about people who live(d) not only Ukraine but who today are also witnessing genocidal massacres throughout the world. The emotional impact is what needs to be felt and film makes emotional moments live as they resonate with the viewers’ emotions.

Some voices, some few subtitles, a lot of silence, fabulous photography of the faces of the prisoners, long endless lines and groups of people, Nazis arresting people, invading quiet homes followed by them setting them aflame — you hear the surprised screams of the people within, men, women and children shoveling and carrying dirt, building fortifications.

August 1941 celebrations with Nazi signs, military and Nazis warmly greeted. Lots of pomp and then a black halt. Switch to lines of tanks moving forward shooting, starting fires, miles and miles a burned autos and trucks, masses and masses of people, pure devastation of burned landscapes, much like we are seeing today as fires destroy our countries. Triumphal Germans allow women to take their prisoner husbands home, smiling, a mere token.

September 24, 1941, Kiev, hanging potsers of Hitler: The Liberator, a peaceful city until the explosion by the Soviets leads to the exterminatinog of the entire Jewish community.

However, even more incredible was the actions taken by the Nazis … SS mobilized a party of 100 Russian war prisoners, who were taken to the ravines… these men were ordered to disinter all the bodies in the ravine. The Germans meanwhile took a party to a nearby Jewish cemetery whence marble headstones were brought to Babii Yar [sic] to form the foundation of a huge funeral pyre. Atop the stones were piled a layer of wood and then a layer of bodies, and so on until the pyre was as high as a two-story house. Vilkis said that approximately 1,500 bodies were burned in each operation of the furnace and each funeral pyre took two nights and one day to burn completely. The cremation went on for 40 days, and then the prisoners, who by this time included 341 men, were ordered to build another furnace. Since this was the last furnace and there were no more bodies, the prisoners decided it was for them. They made a break but only a dozen out of more than 200 survived the bullets of the Nazi machine guns.[38]

July 1944 Soviet troops tour Lviv, Polish Lwów, German Lemberg, Russian Lvov, the largest city in Western Ukraine, historically the center of Galicia, a region now divided between Ukraine and Poland.

Down come the German street signs, up go the Cyrillic signs, down come the posters of Hitler, up go the posters of Stalin. Flowers are offered to new carloads of officers, dancers celebrate, masses and masses of people again crowd into testimonies and for the execution by hanging in the public square of those guilty of the brutal extermination of Soviet citizens and prisoners of war, for the destruction of cities and villages, and the enslavement of the population of Soviet Ukraine.

As if the Ukrainian population had no responsibility for helping kill the Jews, the Gypsies, the mentally ill…there is no mention of that…only masses of onlookers watching as it happens.

On December 2, 1952 the Kiev city council decided to fill the spurs of Babi Yar ravine with industrial waste from the nearby brick factory which was erecting boxlike multistoried apartments.

One is left to wonder, what is the legacy of war and of Babi Yar?

How did Sergei Loznitsa, director/script writer/producer, born on 5 September 1964 in Baranovici (USSR) come to make this film? Was he merely commissioned by the Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial Center which will commemorate the 80th anniversity of this on October 6, 2021?

He grew up in Kiev, and in 1987 graduated from the Kiev Polytechnic with a degree in applied mathematics. Sergei Loznitsa went on to study feature film making at the Russian State Institute of Cinematography (VGIK) in Moscow.

He has already directed 22 internationally acclaimed documentary films and 4 feature films, all of which premiered in the Official Selection of Cannes Film Festival.

His answer illuminates the need for this film:

When I was little, we lived in the Nyvki district of Kiev. There is a forest between Nyviki and the Syretz district, where Babi Yar is located. From the age of 10, several times a week, I used to take a bus from my house to the «Vanguard» swimming pool in Syretz, and come back on foot, through the wooded area and the ravine, occasionally stumbling across the stones with faded inscriptions in a strange language. In fact, I was walking through the remains of the old Jewish cemetery, abandoned at the time, or to be precise, not yet completely raised to the ground by the local authorities. One day, when on my usual route back home, I came across a new stone. This stone had a fresh inscription in Russian, which stated that there would be a monument inaugurated on this very spot. Having read the inscription, I went home to my parents and asked them what had happened in Babi Yar and why was it necessary to put a monument there. I never received a direct answer. Adults tried to avoid the subject, and their answers seemed vague. As far as I know, this was a taboo subject in Kiev in the 70-s. Even in the 50-s, immediately after the war, the tragedy of Babi Yar was covered in a shroud of silence.

Today, they say that Soviet ideology was to blame for this silence, but I think that the problem lies deeper. It’s about human nature in general. Talking about this tragedy makes one feel uncomfortable. The memory of it is shameful and scary. In Vasily Grossman’s «Life and fate» there is a passage — a letter written by a Jewish mother to her son. She wrote it just before being taken to the ghetto. This text has a documentary reference: Grossman quotes the letter from his own mother, who died in the Berdichev ghetto. She wrote that as soon as the Jews were declared «outlaws», her neighbours in the communal apartment threw her out of her room, and she found her possessions piled up in the cellar. It was neither the communist party, nor the Soviet authorities, it was her neighbours who threw her out of the flat. They simply told her that she no longer had the right to live there. The Jews were «against the law».

I study dehumanisation, the loss of humanity by a human being. This is why it is important to begin the documentary about Babi Yar with the German invasion. There was a regime change, and prior to that — a short period of chaos, of lawlessness. It is during this moment, when the true nature of a human is revealed. Without control and pressure from the authorities, in an atmosphere of chaos, it seems that anything is allowed, any action can go unpunished.

I have every reason to believe that back in September 1941, many residents of Kiev had suspected that Jews were going to be killed and not “relocated to the south”. But no one protested. Of course, it is impossible to judge people, who had found themselves in the most extreme and difficult circumstances, but it is possible to reflect upon this whole situation. In fact, it is necessary to think about it. No doubt there were the righteous among them — those who hid the Jews in their houses, who helped them survive. But they were few and far between. This is what scares me. Certain individuals committed heroic acts and risked their lives by helping the Jews, while thousands of others remained indifferent to the fate of the Jews, preoccupied with their own “housing issues” and dividing the remaining Jewish property. Neighbours reported on their neighbours, concierges acted as informants — they used the same lists of residents, which they had previously supplied NKVD with, to report the Jews to the Germans. After the massacre, a few remaining invalids and elderly Jews in the Podol district of Kiev, who were too frail to walk to Babi Yar, were hunted by the local residents, dragged out of their apartments and stoned to death. The locals did it on their own initiative, without any German involvement. I saw the archive documents, describing these atrocities, with my own eyes.

I believe we must learn the truth. The knowledge of history is the best-known defence against chronocide. It is also the only way out of the Soviet/Post-Soviet swamp, where the countries, heirs to the former USSR, find themselves today.

The world premiere of the documentary Babi Yar. Context was held on July 11 in the Séances Speciales section of the Cannes Film Festival. Ukrainian audiences will be able to see this film in the fall during events commemorating the 80th anniversary of the Babyn Yar massacre.

The documentary film Babi Yar. Context was produced by ATOMS & VOID (The Netherlands) by order of Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial Center (Ukraine).

The film received the L’Œil d’or (Golden Eye) award for documentaries. Since 2015, the honor has been awarded to the best documentary presented in one of the sections of the Cannes Film Festival.

Following the award, director Sergey Loznitsa commented, I hope that this award will enable us to reach wider audiences worldwide. And, of course, I very much hope that this film will be screened in Ukraine and will inspire a meaningful discussion. This is particularly important for the country, on whose territory these tragic events took place 80 years ago. Thank you very much! Merci beaucoup!

Babi Yar. Context

Script writer/Director: Sergei Loznitsa

Editors: Sergei Loznitsa, Danielius Kokanauskis, Tomasz Wolski

Sound: Vladimir Golovnitski

Image restoration: Jonas Zagorskas

Producers: Sergei Loznitsa, Maria Choustova

Associate Producers: Ilya Khrzhanovskiy, Max Yakover

Production: ATOMS & VOID for BABYN YAR HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL

CENTER

2021, documentary, 121 min, The Netherlands, Ukraine

contact@atomsvoid.com

© ATOMS & VOID

No comments:

Post a Comment