‘Rehana’, A Feminist Tale as Told by a Man

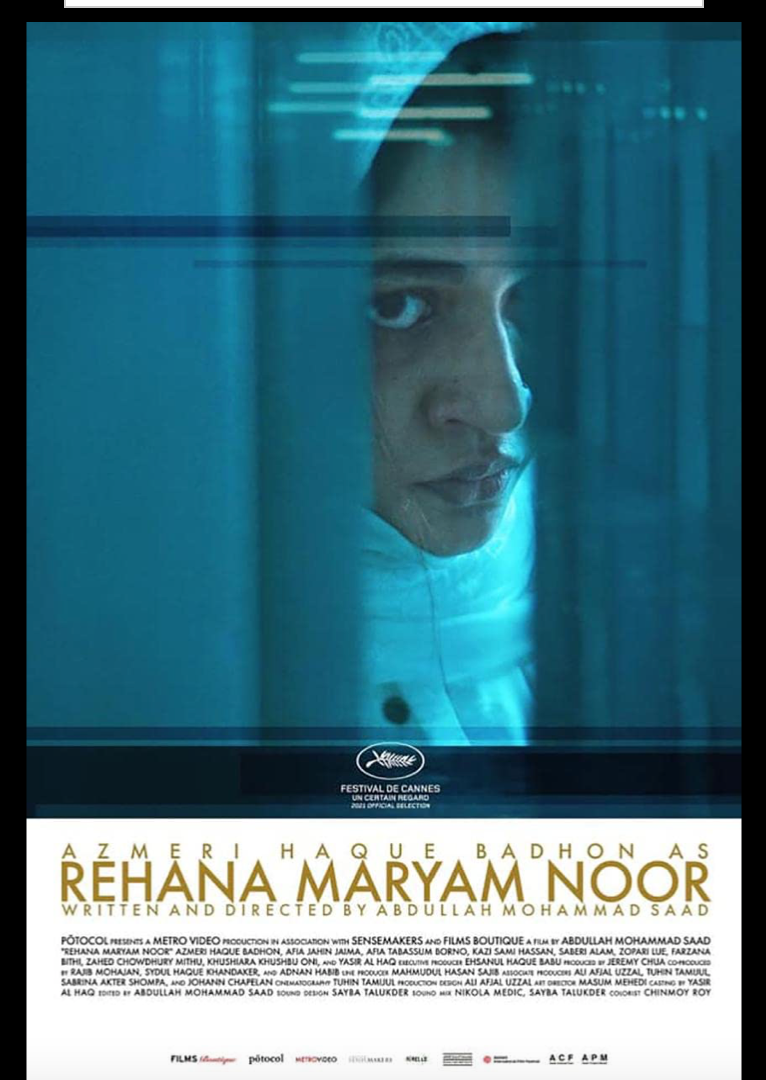

Writer-Director Abdullah Mohammad Saad’s ‘Rehana Maryam Noor’ (aka ‘Rehana’) premiered at the 2021 Cannes Film Festival’s Un Certain Regard. It is the first Bangladesh feature film to make it to Cannes’ official selection — 19 years after Tareque Masud’s Matir Moina (The Clay Bird) was in Directors’ Fortnight, a parallel section, in 2002. It is also Bangladesh’s official submission for Academy Award nomination for Best International Feature.

Watch the trailer here: https://www.imdb.com/video/vi2649277209?playlistId=tt14775748&ref_=tt_ov_vi

The title refers to a woman (brilliantly played by Azmeri Haque Badhon) who is most often seen in closeup in the icy blue, antiseptic and claustrophic setting of the medical college in which she teaches. Rehana is a serious woman, juggling her job as a teacher, doctor, single mother, sister and daughter. Her own daughter Emu is a free-spirited six year being raised in the household of her mother and father and occasionally by her brother and sister and her sister’s husband. She leads a life filled with many responsibilities to keep the family afloat and functioning.

The question this film poses is whether this is a feminist film or a film, made by an “equalist”, which in the end caves into the societal norms of inequality and perpetuates the unjust treatment of females.

There is a most interesting scene about three-quarters of the way into the film, perhaps the only one without Rehana taking center stage, where Rehana’s sister and brother-in-law have a discussion in which the husband calls the wife a “pseudo-feminst” and the wife calls the hysband a “pseudo-liberal”. This is probably the essence of the complex relationship between the sexes. Seeing the relationship between the man and wife as they have their conversation is capped by the husband’s summary of everyone in the end being guilty of splitting from each other and slitting one another’s throats.

We first encounter Rehana from behind as she walks through sterile halls of the medical college where she works, and we find her again as she supervises an exam from which she expels a female student for cheating. When another speaks up on her behalf, Rehana asks her name and tells her to be quiet or she too will be expelled from the room. This is our introduction to Annie, the second character around whom this drama turns.

As Rehana walks to her office, she hears a cry come from the office of her colleague-boss’s office and stops to hear more. She then sees Annie again, this time crying as she exits the boss’s office with her shirt’s button torn off. Rehana takes it upon herself to confront the issue of sexual impropriety which she has just witnessed to the shame of Annie, physically sick to the point of nausea at what has occurred.

At the same time that all of this is going on, Rehana is struggling to make sure her irresponsible brother picks up her daughter from school. Later her daughter’s school calls to report her daughter has bitten a classmate. Before punishing her daughter and making her apologize, she listens as her daughter’s tells her she bit the boy because he is always pinching her.

Faced with two injustices, both related to male privilege, Rehana proceeds to seek justice. She is not only alone in her introverted sense of right and wrong, she is alone because of Annie’s fears of ruining her reputation and facing societal punishment, of putting her family to shame, and failing at the school which costs her family so much sacrifice. Rehana’s lonely quest for justice becomes an obsession. She tells Annie that she will report the incident as happening to herself. And in turn, Annie betrays Rehana and Rehana realizes that perhaps Annie has been seeing the professor at other times as well. The female administrator of the school also is hesitant to make a report which will soil the school’s reputation and lists her reasons, all relating to male privilege and mistrust of female initiatives. Rehana becomes a singular target as she confronts the deeply embedded forces of patriarchy in Bangladeshi society.

As a counterpoint to her workplace harassment issues, she is at first proud of her daughter’s striking back in self-defense. But that too has consequences. If the child does not apologize to the boy she bit, she will be expelled. She is looking forward with great excitement at performing in front of the school when Rehana decides she will not apologize and therefore will not participate in the school performance.

In the end, Rehana uses force against her own child even though she understands the position of women as victims of such violent suppression. She perpetuates the violent repression of women by forbidding her daughter to perform the piece she has worked so hard to perfect. By not explaining to her daughter the reason she was not going to perform, she forces the child to learn that power rules over justice. And it leads to future mistrust among women which disallows the solidarity needed among them to fight sexual based injustice. It leaves the child with the same problem the mother is facing. And in the end, everyone, including Rehana is lying.

Thereafter, her daughter will resent her just as the students resent her for bringing a light upon the systemic repression of female students. Life would be easier if she would just ignore it, allow her daughter to perform in a treasured role in the school play after apologizing to the student, or if she would simply allow the young woman to hide her shame within herself rather than make it public.

On the other hand, something like the slap she gives Annie for betraying the cause of justice, or the proverbial slap a mother gives her daughter in some cultures when her menstrual period begins, as if to warn them that life will be a punishment for being born female, there is a consciousness which takes over in all parties of the injustice done. The lesson she is teaching her child may be a life-saving gesture for the child growing up in that society.

I wanted to know what led the male director and producer to this decidedly female story.

Writer-Director Abdullah Mohammad Saad’s answer:

“I always start with a character rather than a subject. I believe my protagonist eventually guides me to the subject. In this case, I have been obsessing about Rehana for quite some time. She is someone with whom I could personally connect. My three brilliant elder sisters had a huge influence on me while growing up. I have seen them closely as sisters, as daughters, as professionals, and as mothers. I guess I wanted to investigate and share that experience. Also, I have always been very interested in the complex relationship between women and men, and how we treat each other. Perhaps, all of these culminated into Rehana Maryam Noor.

Even though [establishing an equal status for women] has been real slow, but I think the scenario is changing. I am not a very optimistic person but I can see that the deep rooted distrust, fear and anxiety between men and women are getting narrower. Perhaps the greatest revolution of the human history would be to make everyone understand that we are all the same and we have to depend on each other and help each other to survive in this complex world, not the other way around.”

National award-winning critic and curator to festivals worldwide, journalist and the India and South Asia Delegate to the Berlin International Film Festival, Meenakshi Shedde, says, “Can’t wait for sub-continental audiences to see this film. Take a bow, Bangladesh!”

She also says,

“[Saad’s] screenplay is in the same class as Asghar Farhadi’s finest work, in terms of moral complexity. Also, it is rare and thrilling to see such powerful images of strong, financially independent Muslim women in South Asian feature films, especially single mothers; all the more daring for coming from a secular nation with Islam as its state religion.

Indian subcontinental cinema has a long history of male directors being ‘equalists,’ if not feminists. Saad delivers a masterstroke: [Rehana]’s protagonist is not the victim of rape, but a witness, thereby indicting all of us who may be witnesses or aware of rape, but unlike [Rehana], refuse to go all the way till justice is served. More importantly, creating sympathy for the victim or witness is a low-hanging fruit that doesn’t interest Saad. If anything, he goes out of his way to make it challenging for the audience to empathise with his protagonist, even though she is obviously fighting for the right thing. In doing so, Saad raises the bar incredibly high: [Rehana] is not only a fantastic film, it is also a demanding film, yet deeply rewarding, leaving you with a welter of morally complex positions on rape and consent. It is also painful to watch reality reflected: how swiftly women who call out rapists are punished, and in a perverse subcontinental specialisation, how manipulative men swiftly turn the tables, portraying the victims of rape as perpetrators of injustice against men. [Rehana] nearly destroys herself, as well as those around her, in her quest for justice.

As Variety says,

“While the film raises questions of truth and the difficulty of establishing it — especially within the entrenched system of an institution — Rehana herself comes under the moral microscope in terms of her conflicted relations with her students and with Emu. The chain of scenes in which this loving and committed mother engages with her lively, intelligent child (a sparky, winning and eventually troubling performance by young Afia Jahin Jaima) culminates in a closing moment that shows how the cycle of rage perpetuates itself, even when fuelled by noble social convictions.

Indeed, three top Bangladeshi directors have recently addressed #MeToo — Saad, Mostofa Sarwar Farooki’s web series Ladies & Gentlemen that dropped on Zee5 Global on July 9, and Rubaiyat Hossain’s Made in Bangladesh. One could consider them part of a Bangladeshi New Wave, along with several other directors. “

This searing investigation of a woman determined to seek justice raised more questions in my own mind about how and why the writer-director Saad came to filmmaking.

How did you learn to make movies?

I didn’t have formal training. I learned by watching films and reading about them. I also worked as a TV commercial director before I made my first film. It helped me to learn the technical side of filmmaking. I think his journey might encourage upcoming filmmakers in their own journeys.

Did you make many shorts before making a feature?

Yes, I made a couple of short films with my friends.

What brought you into making movies?

It’s hard to explain. I don’t think there was a single reason or incident. I didn’t grow up with movies. Watching films in theatre was not a common practice in my family. I tried to do a lot of other things in my life where I failed. I guess filmmaking grew into me slowly and eventually gave me a sense of purpose.

How did the Singapore Film Festival and meeting Jeremy Chua there change your life?

I will always be grateful to the Singapore Film Festival, especially to Zhang Wenjie. He was the program director of the festival at that time who selected Live from Dhaka. He inspired me a lot.

I met Jeremy [Chua] in the Singapore festival. He also had a film in the competition. We talked a little bit and found some similarities in our approach to screenwriting. After the festival, we began discussing a lot and decided to work together. He is very talented and passionate.

— -

Saad’s debut feature Live from Dhaka won best director and best actor at the Singapore International Film Festival in 2016, and went on to screen at other festivals including Rotterdam and Locarno.

Rehana was produced by Jeremy Chua of Singapore’s Potocol, in association with Bangladesh’s Metro Video. The project was made with the support of the Doha Film Institute Post Production Grant 2020 and the Busan Asian Cinema Fund. It is co-produced by Sensemakers (Bangladesh) and associate produced by Girelle Production (France). Rajib Mohajan, Saydul Khandaker Shabuj and Adnan Habib serve as co-producers, Ehsanul Haque Babu as executive producer and Johann Chapelan as associate producer.

I also wanted to know more about the producer Jeremy Chua and how he chose to become involved in this film. You can watch the uncut interview below.

Double-click on picture to bring up entire interview with jeremy chua and sydney levine

Below are excerpts from an interview Jeremy had previously with Variety, as quoted in text below.

https://variety.com/2021/film/festivals/jeremy-chua-cannes-rehana-film-funding-1235012288/

Jeremy Chua is a Singaporean producer/writer based in Singapore and Paris. Since 2014, when he started his own company, Potocol, a company devoted to Asian auteur films, he has co-produced A Lullaby to the Sorrowful Mystery by Lav Diaz (Silver Bear Alfred Bauer Prize, Berlinale Competition 2016), A Yellow Bird by K. Rajagopal (Cannes Critics Week 2016) and Brotherhood by Pepe Diokno (Karlovy Vary IFF 2016). Potocol is also developing Tomorrow is a Long Time by Jow Zhi Wei (Jerusalem Film Lab 2016), You Are There by Nicole Woodford (SEAFIC 2017), I See Waves by Abdullah Mohammad Saad (ACF Script Development Fund) and is in post-production for Family Events by Ying Liang. In 2017, he was selected as one of Berlinale Talents and was a finalist for the VFF Talent Highlight Award. He is also a programmer at the Pingyao International Film Festival.

Variety: What attracted you to Rehana? How did you meet Saad?

I think even in Asia, a lot of us do not have many chances to be exposed to independent or arthouse Bangladeshi films. But after I saw Saad’s first film, Live From Dhaka at the Singapore International Film Festival in 2016, I realized that there is a lot of talent in Bangladesh. The directing, the dialogues, the cinematography, the acting, the editing, the style; there is a new vision and energy that Saad and his team brought to the screen. I could tell that he understood a darker side of humanity, in both its beauty and vulnerability. Although his storytelling is minimal, his characters are layered with multiple complexities and this organically creates tension and drama. It has a similar sensibility to the kind of films I love. So it was exactly during the festival we discussed and decided to work together to develop and produce his second film.

Sydney Levine: What kind of films do you love?

I love the sort of film about people’s mysteries that occur in life. Today it is easy to get caught up in existence and life’s routines. Films can transform things one knows about but not really is aware of. How bleak reality pushes people to the edge of humanity, to extreme measures. In Singapore the intellectual concept o poverty exists, but we don’t really know it. The film showed a Bangladesh we did not know before though workers are in Singapore but are out of sight for us. The film humanizes them and builds a world where emotional reality becomes real.

The film was done on no budget and I wanted to work on a second film with better structure, getting international partners. Initially we thought it would take place in Thailand and we researched Thailand with the Busan Fund’s money. He had a script idea but when he returned he felt the film had to be about Dhaka. It was a 180 degree turn. It was about a woman who would never back down. She is brought to the edge. It was investigative at first but he got more nterested in knowing her frailty … as a mother as well as a professional.

Sydney: Why are many of your films about women?

It is coincidental. Characters I don’t understand interest me most. In Paris, many of the people I met were women. There are parallels with the feminine world, more honesty, more related to reality — women confront it more strongly, the emotional side…

Sydney: How did you become interested in film?

As a kid I had to struggle emotionally to connect with people; I didn’t understand feelings. Watching films showed feelings, otherwise I had a very inner world. Film was like an epiphany, a touching of God. I understood through them why people behave as they do. There was an emotional communication through film related to parents and friends with problems.

Sydney: When do you choose to work on a movie?

I want to know the characters and have a better understanding of them.

Variety: How did you go about financing the film?

There is no national commissioner in Bangladesh or regional funds around South Asia. At the start, Saad introduced me to a young and upcoming producer in Dhaka, Rajib Mohajan, and together our first step was to apply for the Asian Cinema Fund for Script Development from the Busan [International Film Festival], which we were awarded in 2017. We then spent many months researching and exploring different story ideas. By 2018, we had an advanced draft of the script and applied to participate in the Asian Project Market of Busan IFF. At the market, we met many producers, sales agents and programmers who gave us invaluable feedback; and found partners from France and Norway to apply for European financing. Unfortunately those bids were unsuccessful and we began searching for private equity in Bangladesh. We received a couple of offers but finally decided to work with executive producer Ehsanul Haque, who was extremely supportive of the artistic direction and gave us a lot of freedom to create. We were also supported by members of the crew, volunteers and sponsors. After production, we applied for post- production funding and were supported by the Doha Film Institute’s Post Production Grant 2020. Finally, our French associate producer Johann Chapelan covered our final expenses for deliverables.

Variety: What did the selection in Cannes mean to you?

Any film is a sacrifice and a devotion. It takes up a lot of creative energy, time, commitment, and of course money. So to me the Cannes selection in Un Certain Regard is a validation of Saad’s talent, the fire in his heart, for him to be living in a place that is extremely difficult to make independent films, especially over the last two years. It is a beautiful dream and reminds me to take nothing for granted. This can only be fuel for the next projects I’m working on.

Sydney: What would you like conveyed to the Women’s Conference of the Dhaka Film Festival?

I learned in Bangladesh that there was a very small percentage of women within the structures of power and I hope they will learn how to make changes. I feel the film may empower different aspect of social life. Women should not be defined by the structures that are hurtful, even if it is just impacting another person; to look away or not look away is an important decision. I hope it will allow women to take charge more. Even my own crews are mostly women; there are very few women. I hope younger people will mix

Production companies

· Doha Film Institute (support) — Qatar

· Girelle Production — France

· Metro Video — Bangladesh

· Sensemakers — Bangladesh

· Potocol — Singapore

International Sales Agent: Films Boutique

Distributors

· Grasshopper Film (2022) (USA) (all media)

· Gratitude (2022) (USA) (all media)

Festivals

France 7 July 2021 (Un Certain Regard)

Australia 17 August 2021 (Melbourne International Film Festival)

So. Korea 6 October (Busan Film Festival)

UK 10 October 2021 (BFI London Film Festival)

Saudi Arabia 7 December 2021 (Red Sea Film Festival)

No comments:

Post a Comment