Into a deeply religious mining community, an angel comes. Well, not an angel exactly, more of a saint. And the saint is more of a Christ figure. Even a townsman confuse their only saint with Jesus Christ.

In this stark and beautiful film, the statue of the saint upon a cross has disappeared. Shortly after a mute man appears who seems able to perform miracles and is accepted as the saint come-to-life. This leads to conflicts not to peace. Filmed in the still-operating oppressive Chiatura mine complex in central-western Georgia, Citizen Saint explores the harsh lives of the locals as they cope with the questions of faith.

The miners and Christian hypocrisy do not go together. The struggle between right and wrong as the ruling powers in a small mining town in Georgia connive brings with it the conundrum of faith. A parable for today, this story rings as true as it was when it first occurred.

In regard to the complex themes explored in the film, director Tinatin Kajrishvili says, “Observing how far people can go in search of hope and miracles made me write the script. Unrealized expectations and fear of loss lead people to make extraordinary decisions. It’s an endless circle.”

Reminiscent of Jules Dassin’s 1957 movie, He Who Must Die, although the political backstories differ, both re-enact the passion of the Christ saga in their particular milieu. In He Who Must Die, the back political story is the politics of resistance of the Greeks against the Turks. In this, it is the workers against the capitalist ruling class. While we all know it, the truth as illuminated in both movies still often eludes us. This film reminds us of the struggles we all share.

The stark black and white opening of the film — from the inside of the mine where Berdo (played by Levan Berikashvili) the protagonist lives to be near his son who died in the mine’s collapse, to the outside of hard unforgiving stone cliffs contrasting against a huge sky where Berdo takes the saint (aka foreigner) to view the town from above, to the town where Berdo takes the saint to report in and they enter the sheet shrouded room where the monument’s cross, sans disappeared saint is laid out — the cinematography plays an important part in shaping our response as the story unfolds. The town’s mayor and VIPs measure the saint to be sure he fits the cross, and he leaves it with stigmata on his hands; these sharply contrasted and enigmatic scenes lead the viewer into a mystical and particular Georgian story of a saint who is lost, found and lost again.

Georgia’s Christian roots go deep and this film captures faith as the people adopted it 300 years after Christ, the same time that the Roman Emperor Constantine converted to Christianity leading to the Christianization of the Roman Empire. However, this is not a “faith-based” film. Its plot goes in crazy places, into the townspeople’s lives who have been praying with no salvation for years until the saint comes to life. Again, in contrast to He Who Must Die, written by Nikos Kazantzakis, who also wrote The Last Temptation of Christ one of the most controversial books of all time and often on “banned book” lists, Citizen Saint does not leave you with the compassion and catharsis of the Passion. It leaves you with the supposition that faith does not really matter in truth, only in fiction, as a sop for the masses, and yet there remains the elusive wish for righteousness.

The exploitation and sacrifice, even martyrdom, of the miners is exemplified by the saint himself, said to have been a miner who died and whose body miraculously did not decay but calcified and became the statue of the only saint worshipped in this village.

The magnificent monochrome cinematography by Krum Rodriguez, (which won Best Cinematography at the Asian World Film Festival, its U.S. premiere) focuses on the mines, rusting mining equipment, ladders to the saint, sheets covering the surroundings where the saint on the cross lies waiting for restoration, outside in an unforgiving wild landscape, and in reconstructed artwork. All bring to mind the industrial photography of Lewis Hines or the cinematography of Tarkofsky, Bela Tarr and Angelopolous. It transports the viewer from the mundane to the sublime.

The music also transcends. The score of Tako Jordania punctuates and carries the mysticism of the story. A single long-held trumpet note; a motif going from two notes to four, repeated with a sustained interval and then repeated again; at the sound of the train going into the mountain a religious longhorn is followed by a chorale combining with an almost rabbinic song. The lone horn again — the mine will collapse again.

Tako Jordania, the composer, began not only composing but by working with children with hearing problems and with children who were on the autistic spectrum. She helped them begin to speak with the help of music. Says Kajrishvili: “Her attitude to the world of sound was very interesting for me, as I have the main character, who doesn’t talk and we don’t know what he hears (he hears thoughts).” Jordania also has scored eight shorts between 2010 and 2017 and one feature in 2017. Where has she been an what has she been doing between 2017 and 2023?

Also admirable is the beautiful faded socialist art on walls and on building facades. It was surprising to learn they had been painted specifically for this film. Giorgi Gordzamashvili gets credit as the production designer. I would buy this artist’s work in an instant. Gordzamashvili was also the production designer on Tinatin Kajrishvili’s 2018 film Horizon.

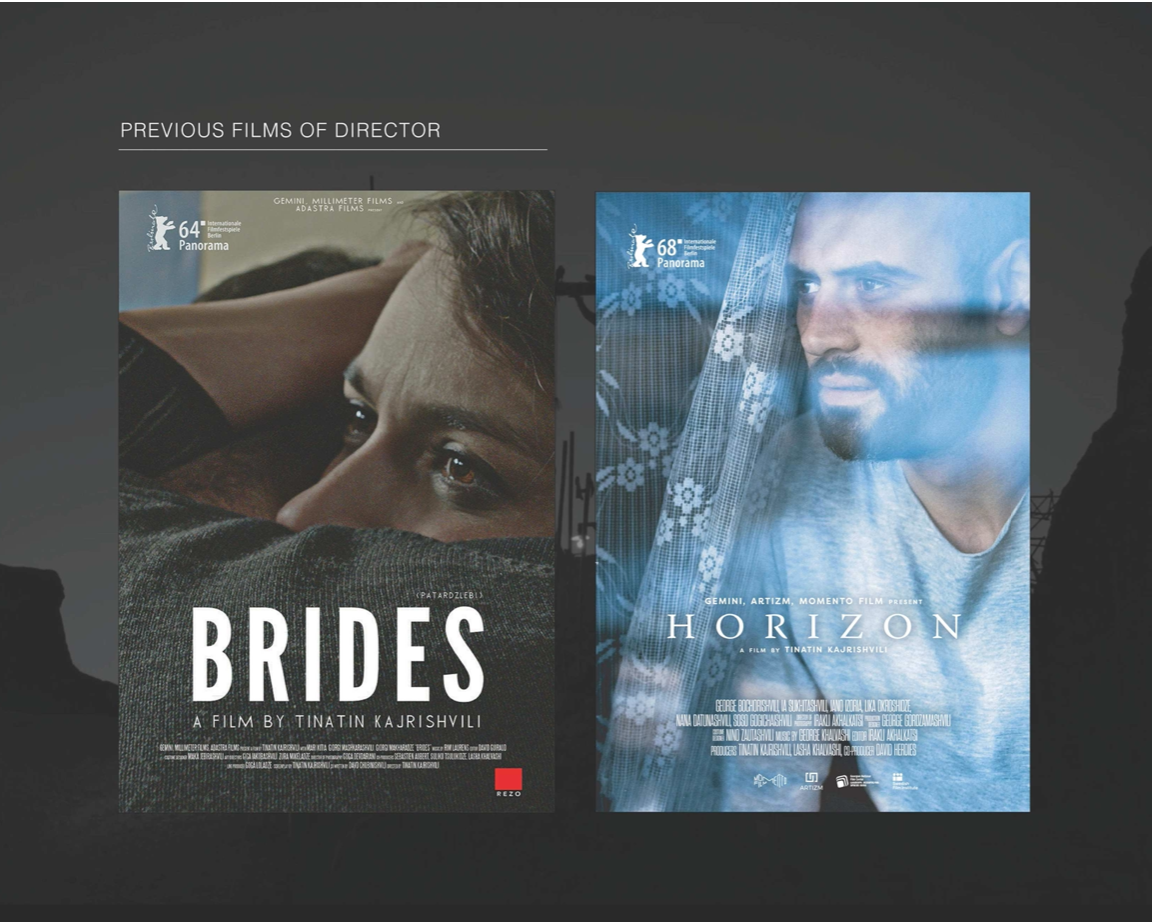

Known in Germany and throughout Europe for her Berlinale titles Brides(winner of Panorama Audience Award) and Horizon, Tinatin Kajrishvili directed and cowrote (with Basa Janikashvili) Citizen Saint, her third feature. She is not known in the U.S., but this film should put her on the map.

Watch the international trailer here. https://vimeo.com/artizm/cstrailer?share=copy

Citizen Saint premiered at Karlovy Vary International Film Festival in 2023 and was recently nominated for Best Film at the 16th Asia Pacific Screen Awards. It won for Best Cinematography at the Asian World Film Festival in Los Angeles, its North American premiere.

In Georgian with English subtitles, the film is produced by Georgia’s Lasha Khalvashi at Studio Artizm and Tinatin Kajrishvili for Germini. It is a coproduction with France’s Mandra Films and Bulgaria’s Chouchkov Brothers. International sales are by Studio Artizm. U.S. is available.

No comments:

Post a Comment