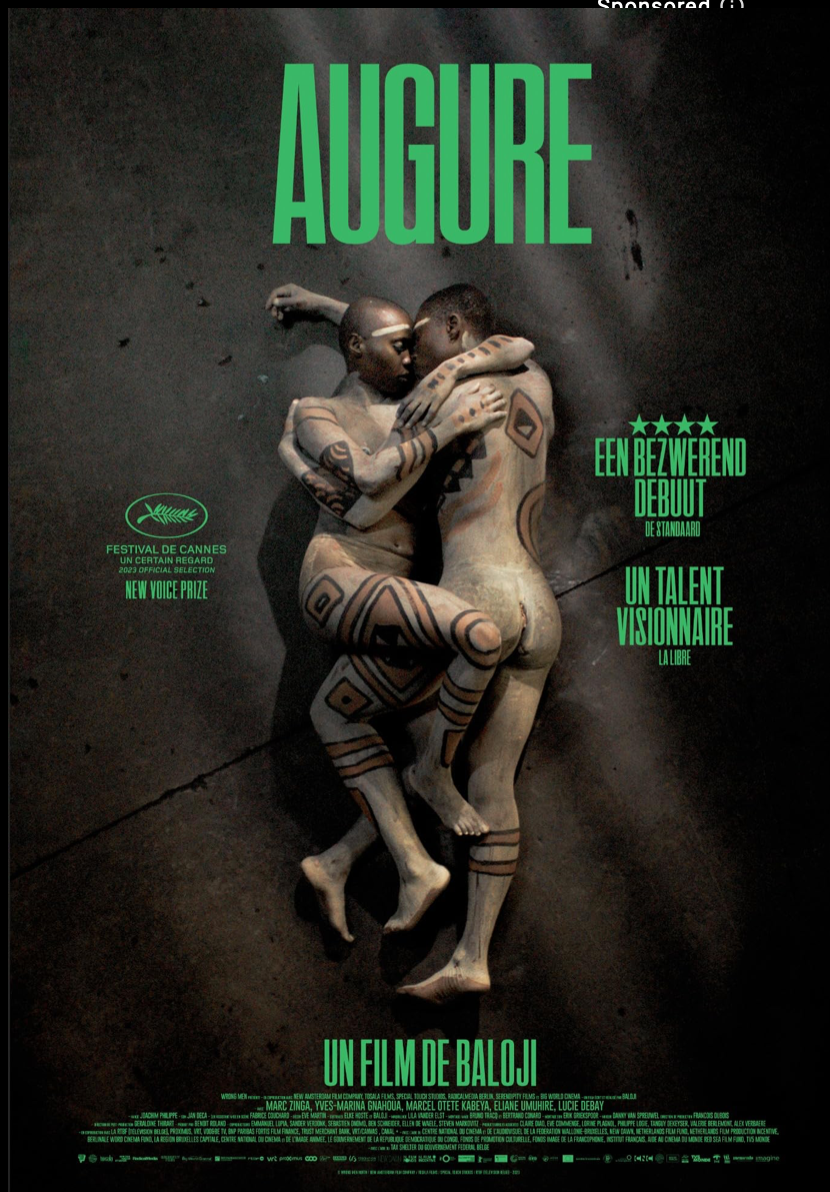

The director Baloji is currently in L.A. showing his film and speaking to the Academy members and press about his Cannes Award winning debut feature ‘Omen’ (aka ‘Auguri’). He himself is outgoing, beautifully mannered and dressed, a treat to speak with as he so gracefully articulates his creative sources. While he is Belgian, he was born in the Democratic Republic of Congo and this film speaks to us of Congo as much as it credits Belgium today, a multicultural democracy.

After spending 18 years in Belgium, a young Congolese man named Koffi returns with his pregnant Belgian wife to his birthplace of Kinshasa to introduce her to his family and give them the honors due as a first son. However their glacial welcome reminds him that homeland culture with its family secrets and sorcery has frozen his status as a Zabolo, one who wears the mark of the devil. The intricacies of identity, culture, and belief systems is captured within the context of magical realism in a deeply rich, original and visually captivating style.

Watch the trailer here.

The story takes hold of the audience as it is unfolds through intertwined stories of four Congolese characters acting ensemble who are labeled witches or sorcerers.

What is your connection to these stories of sorcery and witchcraft?

It is personal and extremely dear to me, having been considered a sorcerer myself.

In Swahili, my name, Baloji, semantically means “man of science”. With the Christian colonizers arriving in Africa, it became “man of black science” (healer) and then “man of black magic” (witch doctor). In the last few years, it has become a synonym for sorcerer, and is basically the same as being called “devil” or “demon” in Africa itself. It’s not an easy name to live with. It’s an awful name, really, being named “Demon” in Belgium. Because people used to label me as a sorcerer, I’ve always been fascinated by witchcraft and by people who are seen as “different”.

That’s why Koffi, the main character, has a port-wine stain on his face: I wanted to visualize the weight of that label.

Why did your parents name you this?

For personal reasons I prefer not to discuss except to say my father was ill at the time I was born.

I understand. When loved ones are ill, the family will do anything they can to help heal their beloved.

So as a kid, you were called a sorcerer. Does making this movie help you?

Yes, I’ve finally accepted that maybe my name is also what I am. In Congo, when I learned that originally my name meant “man of science,” it became something positive. It wasn’t until European Christian colonialism came into the picture that the word “baloji” turned into something negative.

(Editor parenthesis: How coincidental that those with a so-called “christian”, but dumb-downed, mentality today in the U.S., the ones so against immigration of formerly colonized people are the same people who are against acknowledging scientific sources and cures for global warming, famine, COVID, critical racism, sex education, et al.)

So now I can deal with it. And when I started making movies, I decided to put some magical realism into them. It’s part of me, so it must be part of my cinema language.

What statement did you intend to make with the story?

The more I reflected on witchcraft and sorcery and on all the ways that society finds to define and fight against those who are “different”, the more I wanted to focus on the effects of that.

I wanted to show how society is structured for men, and how they try to control women’s bodies. What happens when a young girl doesn’t want to have kids. Being a 35-year-old woman and not having children is considered “not right” in Europe as well as in Africa. A woman gets completely discarded when she grows old. I’ve been studying feminism and I think it’s my obligation — because as a man and therefore part of the problem — that I be a part of the solution as well.

In the same way that racism is a white people’s issue: it can’t be solved unless white people start talking about it.

The topic of family is one of the most important in the film.

I think the family is the laboratory of society. Everything you can find in a family is a reflection of society. So it means you have to fight and accept the same things in your own family as you do in society on a bigger scale.

I wanted to show different forms of assignation, in order to approach the subject in a larger way. For a woman like Tshala, Koffi’s sister who lives a life of polyamory, being labeled a witch is a bigger burden than for a man.

For an older woman like Mujila, Koffi’s mother, it’s even worse. Really the one I think is the true protagonist is the mother…and then the sister.

Paco, one of the main characters, is a young boy who is also considered a sorcerer. Paco is a young shégué (street urchin) on the other side of town who’s haunted by his little sister’s death and mired in a gang war that prevents him from grieving. Koffi and he are both witch children, cursed sons who need to be exorcised. In Paco’s case, when parents have money issues, it’s sometimes believed to be the fault of their youngest children who have supposedly cursed the family. The parents often send these kids away, and they end up on the streets. This is what happened to Paco. But he deals with his assignation in a way very different from the protagonist Koffi, who is ashamed and thinks it’s the worst thing that ever happened to him. Paco has learned to use it to his advantage: he does magic tricks and scares people. He takes a certain pride in his assignation.

In fact, throughout the movie Paco and Koffi appear in adjacent scenes as mirrors of each other. Both have epileptic attacks, often taken as a sign of possession by the devil. When Paco suffers such an attack, the next scene shows Koffi awakening. You will notice throughout the movie that they are always scenically joined together.

You’ve done many different things in your life: you were part of successful Belgian hip-hop group Starflam; you’ve acted. How did you become a film director?

From 1998 to 2006, I lived above a music and video store in Brussels. Every day, I would go pick up my mail downstairs and start talking about movies with the guys who hung around in the store. They made me discover films like Gus Van Sant’s Gerry, that had a very different rhythm to them. That was my film school. For years, I would watch a movie every day. And since I was already very interested in music, fashion and art direction, film felt like the perfect fit for me, because it combined all of my passions into one art form.

As a musician, not a director, how did you secure funding for this first feature?

Because I’m a musician, for a long time I wasn’t taken seriously as a director. I wasn’t part of the “film family.” So a lot of people in the industry and the press were very surprised when my film got selected for

Cannes. And now for the Oscars too!

It was very difficult to convince those in the film industry that I was able to be a filmmaker, but I made commercials and music videos. Germany and the Berlinale World Film Fund funded it based on my short film Zombies which won many prizes in Germany. You can see it here on YouTube.

It was also diffficult write a filmic synopsis for this film which I needed to finance it. I pitched it as the story of Koffie and his return to Congo. Koffie is apparently the main protagonist, but he isn’t, in reality. His storyline ends after 20 minutes.

I got more and more interested in the voices of the other characters, who do not have the luxury of being able to come and go in the same way he does. The real victims in this world are the ones who can’t leave. That’s why the movie ends with the character of Koffie’s sister.

I want to return to where you mentioned the port-wine birthmark on the face of Koffi. Your use of colors throughout the film is very striking.

I have synesthesia. To me, everything is connected to color. Sounds, moods — they all have colors in my head. And so all the characters in the movie also have their own color: for Koffi, it’s dark red — like his port-wine stain. Paco is associated with pink, etc. You can see it in the typeface I used to present their names on screen, but also in the color filters we used.

And in the music, too. I only used chords that I felt were connected to certain colors. For instance, I like the music of Eric Satie who often writes in C minor. To me that is blue, a color of melancholia, or the blue at the base of a candle flame, very dynamic and determined.

How did you create the music for Omen?

Very early on in the process, I realized the recording artist music I usually make wouldn’t fit the film. As a recording artist, I always use vocals, but in this film they would just be too much. There is already a lot of information in the image. So I kept the music in the film quite subtle. But then I also

recorded four albums with songs that wouldn’t appear in the film.

Each album is written from a different character’s point of view. It was a great opportunity to create backstories for the characters, which could help the actors. But mostly, it was an exercise in empathy for me. It made me love and understand each one of my characters.

The first is Koffi (Marc Zinga, seen in Cannes two years ago in Tori and Lokita), a Congolese Belgian returning to his birthplace for the first time in almost two decades after being banished to Europe because he was born with a birthmark.

The second is about Koffi’s sister Tshala played by Eliane Umuhire (Neptune Frost in Cannes Directors’ Fortnight 2021), Tshala’s album is all about female sexuality. As a man, it took a lot of reading and studying to be really able to understand the dynamics at play.

The third introduces Paco (the first role of Marcel Otete Kabeya) a teen antibiotic dealer who is the leader of a group of outcasts who all dress in pink drag to honor his dead sister.

The fourth is Mama Mujila’s (steely-eyed Yves-Marina Gnahoua, a theatre actress who starred in the hard-hitting documentary That Which Does Not Kill) story of patriarchal trauma and the real reason she was forced to send him away.

In the film, sometimes the kitchen is green and sometimes gray, depending upon what is happening. I feel moods and hear music in colors. My color associations are very personal to me. Others with synethesia associate other colors to their senses.

Sometimes synesthesia feels like a disease, but I try to have fun with it.

(Editor: Baloji is in good company. Nikola Tesla had it. Beyoncé is said to have Chromesthesia or sound-to-color synesthesia. Duke Ellington, Billie Ellish and Kanye West, Mary J. Blige, Pharrell Williams, Billy Joel, Franz Lizst and Hans Zimmer all have or had various forms of the condition. Marilyn Monroe had it with taste-to-color and Proust has another sort of taste-to- emotion.)

The pinks of Paco were outstanding…as were the bright colored dresses of the three women when Koffi and Alice first come to meet the family… Can you talk more about the costumes?

Together with Elke Hoste, I also designed the costumes for the film. They blend elements from different cultures. For instance the mother, Mujila, always wears lace. Lace is very Belgian. The techniques were introduced to Congo by the Belgians but they used raffia to create the designs, not the fine threads used in Belgium The mother is always dressed with lace and a the sober brown of raffia.

I created a cultural triangle. There are obviously lots of elements from Central Africa, but there’s also an influence from American heritage: the costumes in the parade are inspired by Mardi Gras — we actually went

to New Orleans to create the masks. What I discovered there was that the origin of their own customs including music began in the place they named “Congo Square”!

So this depiction completes a full circle as well as a triangle within the circle.

We also took inspiration from the “Gilles,” the famous folklore characters

who appear in the carnival parade of Binche in Belgium. I also used Belgian surrealist painters like Magritte as an influence, for example in the opening and closing scenes.

What does it mean for you to be able to come to L.A. with your first feature film (after winning New Voice Prize at Cannes)?

It is interesting and challenging to talk about my next movie with the people I meet here when the first one has not yet completed its final phase of release. It’s schizophrenic in a way.

It is very important for all of Central Africa to have a film from Congo represented at the Oscars. It is extremely big! I am from a country where there is no film culture….not in all of Central Africa. Congo has no Academy [AMPAS] standing at all, so it is good that Belgium submitted this film.

You are, as far as I know, the only representative of a film from Africa here and some really good films from Africa are hoping to get shortlisted.

It is also very impressive that your Academy Screening and post-screening Q&A is being sponsored by Mahershala Ali (Moonlight, Greenbook). Maybe we will see him in your next movie. You have an advantage by being here in L.A.

Thank you! If I return to L.A., I will bring you a box of the best Belgian truffles!

*****************

Rapper turned filmmaker Baloji is Belgian-Congolese. He was born in 1978 in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of Congo, and lives in Belgium. He is an award-winning musician, filmmaker, polymath, art director, and costume designer. He transforms his own Belgian-Congolese heritage to original forms and we hope to new heights as well for a long future of success.

Omen follows several well-received short films that have been distributed worldwide, including Zombies (2019).

As a musician, Baloji has released two critically acclaimed albums and two EPs. The latest, Avenue Kaniama, was released on Bella Union Records (Father John Mistry, Fleet Foxes).

**********

International sales agent Memento has licensed the film to Utopia for U.S. to release theatrically early 2024, Stadtkinoverleih for Austria, Imagine for Benelux, Pan Distribution for France, Grandfilm for Germany, I Wonder Pictures for Italy, HHG for Russia, Filmin for Spain, Outside the Box for Switzerland, AYA Films for U.K.

Omen is produced by Wrong Men (Belgium), in co-production with New Amsterdam Film Company(the Netherlands), Tosala Films (D.R. Congo), Special Touch Studios (France), Radical Media(Germany), Serendipity(Belgium) and Big World Cinema (South Africa).

Further support has come from BNP Paribas Fortis Film Finance (co-production), Radio Télévision Belge Francophone (RTBF) (co-production), Proximus (co-production), VOO (co-production), BE TV (co-production), VRT / Canvas (co-production), Canal+ (co-production), Centre du Cinéma et de l’Audiovisuel et des Télédistributeurs Wallons (support), Tax Shelter du Gouvernement Fédéral Belge (support), Nederlands Filmfonds (support), Netherlands Film Production Incentive (support), The Berlinale World Cinema Fund (support), Région de Bruxelles-Capital (support), Fonds de Promotion Culturelle (FPC) (support), Fonds Images de la Francophonie(support), Centre national du cinéma et de l’image animée (CNC) (support), TV5MONDE (participation), Institut Français (support), Red Sea Film Fund(support)

*************

This is Belgium’s 48th Oscar submission. Belgium’s submissions have received eight nominations but no wins. Lukas Dhont’s Close was nominated last year.

No comments:

Post a Comment